Numeral system

| Numeral systems by culture | |

|---|---|

| Hindu-Arabic numerals | |

| Western Arabic (Hindu numerals) Eastern Arabic Indian family Tamil |

Burmese Khmer Lao Mongolian Thai |

| East Asian numerals | |

| Chinese Japanese Suzhou |

Korean Vietnamese Counting rods |

| Alphabetic numerals | |

| Abjad Armenian Āryabhaṭa Cyrillic |

Ge'ez Greek Georgian Hebrew |

| Other systems | |

| Aegean Attic Babylonian Brahmi Egyptian Etruscan Inuit |

Kharosthi Mayan Quipu Roman Sumerian Urnfield |

| List of numeral system topics | |

| Positional systems by base | |

| Decimal (10) | |

| 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 20, 24, 30, 36, 60, 64 | |

| Non-positional system | |

| Unary numeral system (Base 1) | |

| List of numeral systems | |

A numeral system (or system of numeration) is a writing system for expressing numbers, that is a mathematical notation for representing numbers of a given set, using graphemes or symbols in a consistent manner. It can be seen as the context that allows the symbols "11" to be interpreted as the binary symbol for three, the decimal symbol for eleven, or a symbol for other numbers in different bases.

Ideally, a numeral system will:

- Represent a useful set of numbers (e.g. all integers, or rational numbers)

- Give every number represented a unique representation (or at least a standard representation)

- Reflect the algebraic and arithmetic structure of the numbers.

For example, the usual decimal representation of whole numbers gives every whole number a unique representation as a finite sequence of digits. However, when decimal representation is used for the rational or real numbers, such numbers in general have an infinite number of representations, for example 2.31 can also be written as 2.310, 2.3100000, 2.309999999…, etc., all of which have the same meaning except for some scientific and other contexts where greater precision is implied by a larger number of figures shown.

Numeral systems are sometimes called number systems, but that name is ambiguous, as it could refer to different systems of numbers, such as the system of real numbers, the system of complex numbers, the system of p-adic numbers, etc. Such systems are not the topic of this article.

Contents |

Types of numeral systems

The most commonly used system of numerals is known as Arabic numerals or Hindu-Arabic numerals. Two Indian mathematicians are credited with developing them. Aryabhata of Kusumapura developed the place-value notation in the 5th century and a century later Brahmagupta introduced the symbol for zero.[1] The numeral system and the zero concept, developed by the Hindus in India slowly spread to other surrounding countries due to their commercial and military activities with India. The Arabs adopted it and modified them. Even today, the arabs called the numerals they use as 'Rakam Al-Hind' or the Hindu numeral system. The arabs spread it to the western world due to their trade links with them. The western world modified them and called them as the Arabic numerals.

The simplest numeral system is the unary numeral system, in which every natural number is represented by a corresponding number of symbols. If the symbol / is chosen, for example, then the number seven would be represented by ///////. Tally marks represent one such system still in common use. The unary system is only useful for small numbers, although it plays an important role in theoretical computer science. Elias gamma coding, which is commonly used in data compression, expresses arbitrary-sized numbers by using unary to indicate the length of a binary numeral.

The unary notation can be abbreviated by introducing different symbols for certain new values. Very commonly, these values are powers of 10; so for instance, if / stands for one, − for ten and + for 100, then the number 304 can be compactly represented as +++ //// and the number 123 as + − − /// without any need for zero. This is called sign-value notation. The ancient Egyptian numeral system was of this type, and the Roman numeral system was a modification of this idea.

More useful still are systems which employ special abbreviations for repetitions of symbols; for example, using the first nine letters of the alphabet for these abbreviations, with A standing for "one occurrence", B "two occurrences", and so on, one could then write C+ D/ for the number 304. This system is used when writing Chinese numerals and other East Asian numerals based on Chinese. The number system of the English language is of this type ("three hundred [and] four"), as are those of other spoken languages, regardless of what written systems they have adopted. However, many languages use mixtures of bases, and other features, for instance 79 in French is soixante dix-neuf (60+10+9) and in Welsh is pedwar ar bymtheg a thrigain (4+(5+10)+(3 × 20)) or (somewhat archaic) pedwar ugain namyn un (4 × 20 − 1). In English, you could say "four score less one", as in the famous Gettysburg Address representing 87 as "four score and seven years ago".

More elegant is a positional system, also known as place-value notation. Again working in base 10, ten different digits 0, ..., 9 are used and the position of a digit is used to signify the power of ten that the digit is to be multiplied with, as in 304 = 3×100 + 0×10 + 4×1. Note that zero, which is not needed in the other systems, is of crucial importance here, in order to be able to "skip" a power. The Hindu-Arabic numeral system, which originated in India and is now used throughout the world, is a positional base 10 system.

Arithmetic is much easier in positional systems than in the earlier additive ones; furthermore, additive systems need a large number of different symbols for the different powers of 10; a positional system needs only ten different symbols (assuming that it uses base 10).

The numerals used when writing numbers with digits or symbols can be divided into two types that might be called the arithmetic numerals 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 and the geometric numerals 1,10,100,1000,10000... respectively. The sign-value systems use only the geometric numerals and the positional systems use only the arithmetic numerals. The sign-value system does not need arithmetic numerals because they are made by repetition (except for the Ionic system), and the positional system does not need geometric numerals because they are made by position. However, the spoken language uses both arithmetic and geometric numerals.

In certain areas of computer science, a modified base-k positional system is used, called bijective numeration, with digits 1, 2, ..., k (k ≥ 1), and zero being represented by an empty string. This establishes a bijection between the set of all such digit-strings and the set of non-negative integers, avoiding the non-uniqueness caused by leading zeros. Bijective base-k numeration is also called k-adic notation, not to be confused with p-adic numbers. Bijective base-1 is the same as unary.

Positional systems in detail

In a positional base-b numeral system (with b a positive natural number known as the radix), b basic symbols (or digits) corresponding to the first b natural numbers including zero are used. To generate the rest of the numerals, the position of the symbol in the figure is used. The symbol in the last position has its own value, and as it moves to the left its value is multiplied by b.

For example, in the decimal system (base 10), the numeral 4327 means (4×103) + (3×102) + (2×101) + (7×100), noting that 100 = 1.

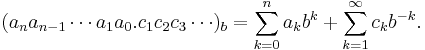

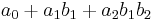

In general, if b is the base, we write a number in the numeral system of base b by expressing it in the form anbn + an − 1bn − 1 + an − 2bn − 2 + ... + a0b0 and writing the enumerated digits anan − 1an − 2 ... a0 in descending order. The digits are natural numbers between 0 and b − 1, inclusive.

If a text (such as this one) discusses multiple bases, and if ambiguity exists, the base (itself represented in base 10) is added in subscript to the right of the number, like this: numberbase. Unless specified by context, numbers without subscript are considered to be decimal.

By using a dot to divide the digits into two groups, one can also write fractions in the positional system. For example, the base-2 numeral 10.11 denotes 1×21 + 0×20 + 1×2−1 + 1×2−2 = 2.75.

In general, numbers in the base b system are of the form:

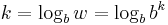

The numbers bk and b−k are the weights of the corresponding digits. The position k is the logarithm of the corresponding weight w, that is  . The highest used position is close to the order of magnitude of the number.

. The highest used position is close to the order of magnitude of the number.

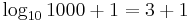

The number of tally marks required in the unary numeral system for describing the weight would have been w. In the positional system the number of digits required to describe it is only

, for

, for  . E.g. to describe the weight 1000 then four digits are needed since

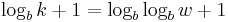

. E.g. to describe the weight 1000 then four digits are needed since  . The number of digits required to describe the position is

. The number of digits required to describe the position is  (in positions 1, 10, 100,... only for simplicity in the decimal example).

(in positions 1, 10, 100,... only for simplicity in the decimal example).

| Position | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | −1 | −2 | . . . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Digit |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Decimal example weight | 1000 | 100 | 10 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | . . . |

| Decimal example digit | 4 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | . . . |

Note that a number has a terminating or repeating expansion if and only if it is rational; this does not depend on the base. A number that terminates in one base may repeat in another (thus 0.310 = 0.0100110011001...2). An irrational number stays unperiodic (infinite amount of unrepeating digits) in all integral bases. Thus, for example in base 2, π = 3.1415926...10 can be written down as the unperiodic 11.001001000011111...2.

Putting overscores, n, or dots, ṅ, above the common digits is a convention used to represent repeating rational expansions. Thus:

- 14/11 = 1.272727272727... = 1.27 or 321.3217878787878... = 321.3217̇8̇.

If b = p is a prime number, one can define base-p numerals whose expansion to the left never stops; these are called the p-adic numbers.

Generalized variable-length integers

More general is using a notation (here written little-endian) like  for

for  , etc.

, etc.

This is used in punycode, one aspect of which is the representation of a sequence of non-negative integers of arbitrary size in the form of a sequence without delimiters, of "digits" from a collection of 36: a–z and 0–9, representing 0–25 and 26–35 respectively. A digit lower than a threshold value marks that it is the most-significant digit, hence the end of the number. The threshold value depends on the position in the number. For example, if the threshold value for the first digit is b (i.e. 1) then a (i.e. 0) marks the end of the number (it has just one digit), so in numbers of more than one digit the range is only b–9 (1–35), therefore the weight b1 is 35 instead of 36. Suppose the threshold values for the second and third digits are c (2), then the third digit has a weight 34 × 35 = 1190 and we have the following sequence:

a (0), ba (1), ca (2), .., 9a (35), bb (36), cb (37), .., 9b (70), bca (71), .., 99a (1260), bcb (1261), etc.

Unlike a regular based numeral system, there are numbers like 9b where 9 and b each represents 35; yet the representation is unique because ac and aca are not allowed – the a would terminate the number.

The flexibility in choosing threshold values allows optimization depending on the frequency of occurrence of numbers of various sizes.

The case with all threshold values equal to 1 corresponds to bijective numeration, where the zeros correspond to separators of numbers with digits which are non-zero.

See also

|

References

- ^ Hindu Arabic Numerals by David Eugene Smith Google Books)

- Georges Ifrah. The Universal History of Numbers : From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer, Wiley, 1999. ISBN 0-471-37568-3.

- D. Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming. Volume 2, 3rd Ed. Addison–Wesley. pp. 194–213, "Positional Number Systems".

- A. L. Kroeber (Alfred Louis Kroeber) (1876–1960), Handbook of the Indians of California, Bulletin 78 of the Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution (1919)

- J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, London and Chicago, 1997.

- Hans J. Nissen, P. Damerow, R. Englund, Archaic Bookkeeping, University of Chicago Press, 1993, ISBN 0-226-58659-6.

- Denise Schmandt-Besserat, How Writing Came About, University of Texas Press, 1992, ISBN 0-292-77704-3.

- Claudia Zaslavsky, Africa Counts: Number and Pattern in African Cultures, Lawrence Hill Books, 1999, ISBN 1-55652-350-5.

External links

- Numerical Mechanisms and Children's Concept of Numbers

- Software for converting from one numeral system to another

- Online conversion of fractional numbers between numeral systems

|

|||||||||||